|

| Red-headed Woodpecker, NBP |

Random events such as hurricanes, fires, disease outbreaks, cold snaps, tornadoes, accidental shooting and stochastic genetic effects * (defined at article end) disproportionately threaten small populations with extinction versus larger populations. For this reason endangered species such as the Black-footed Ferret, California Condor, Whooping Crane, Kirtland's Warbler, Red-cockaded Woodpecker, etc., have received significant amounts of management and volunteer citizen assistance with great success.

The Ivory-billed (IBWO) is in danger of extinction, and as with other species, it could respond favorably to simple habitat management. Basic and relatively inexpensive, volunteer field work can assist Ivory-bills. Since there are so few IBs left even a few 10 acre habitat improvement projects can be helpful, for example, in concentrating food resources to assist in the successful fledging of young.

This article examines just one of the many possible random events, a single hurricane, that can eventually contribute to the Ivory-billed's demise. There are many types of deleterious random events; during any decade there is a probability that several can occur in succession. Habitat management action can increase the numbers of Ivory-bills helping them withstand this inevitable series of events.

|

| Hurricane Laura, CAT 4 = Red, CAT 2 = Yellow, NBP |

Several New World bird species have been lost or pushed closer to extinction with hurricanes being a late stage or final driver. Some of the most rapid and devastating impacts on the fauna and flora are when two hurricanes hit the same area in the same season. In 2020 three hurricanes and two tropical storms hit the US state of Louisiana (LA). Two of these hurricanes followed a similar path. The paths went through some areas that have several, recent, sighting reports of Ivory-billed Woodpecker(s).

|

| Nurse Stump, NBP |

Louisiana is considered by several modern field researchers to be the state with the most Ivory-bills remaining. The last unequivocal small breeding population of Ivory-bills was in northeast LA in the 1930s. However there certainly must have been 21st century breeding in LA and in other states if one accepts the best recent sightings. Some of these sightings are supported by peer-reviewed papers, videos of birds that are, or are likely IBWOs, and other varied data sets such as audio recordings, roost measurements and more.

|

| Singer Tract, LA 5/1937 Rainey Lake courtesy USFWS |

Our first example of the double hurricane phenomenon was the extinction of Saint Kitt's Bullfinch by the "Great Hurricane" of 8/7/1899 followed by another on 8/30/1899. This mysterious island subspecies was only encountered one time after that.

Cozumel Thrasher numbers already reduced by habitat destruction and prior Mexican hurricanes was last seen in 2004. In 2005 Hurricanes Emily and Wilma hit Cozumel and there are no confirmed sightings after that.

The Bahamian Nuthatch was described by James Bond, the American ornithologist (who was friends with Ian Fleming) as common in the pine forests of Grand Bahama Island. The cavity-nester, was in decline for years due to habitat destruction, fires and hurricanes.

A 2004 survey optimistically estimated that up to 1,800 birds could still exist but after a series of hurricanes only 23 birds were found in 2007.

In 2016 Hurricane Matthew, one of the more powerful hurricanes in many years hit the Bahamas reducing the species to a confirmed 2 to 5 birds. In 2019 the powerful and slow-moving Hurricane Dorian hit the same area; the species is now very close to extinction. Certainly, genetic variability is critically low, and functional extinction must be considered.

Three New World Picidae taxa, cavity nesters as all are, have also suffered from hurricanes, two are extinct. The West Indian Woodpecker subspecies of Grand Island Bahamas was never seen again after the hurricane of 2004. The subspecies of San Salvador Island has been closely studied with the population dropping on average 60 to 65% after hurricanes of Category 2 or higher. Numbers precipitously drop from 240 to 90 on average.

The Bermuda Flicker may have persisted until human visitation of the island according to a brief reference by explorer and governor John Smith in the 1600's; extinction occurred in the Holocene of unknown causes.

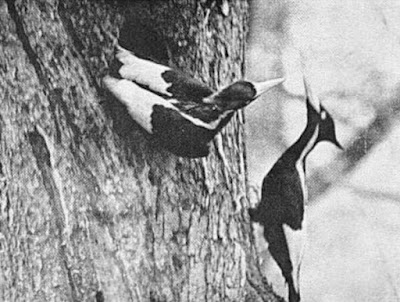

Historically several Ivory-billed roost or nest trees were well observed and at least two of them were snapped by storms; some or all the birds were not seen again.

The last Singer Tract, LA roost under observation by Jesse Laird was felled in a "storm". In the late 1960s a Florida IB roost was snapped in a "storm" at the roost hole. In the FL case the two birds were not seen again but the female IB in LA may have been seen wandering around.

The literature describes IB nest characteristics. The tree diameter at the cavity height was measured in a few cases and averaged ~ 19 inches. The cavities themselves were often vase shaped; ~14 to 30 inches deep. Some nests and roosts are in a deadened part of the tree, some not. IB nests and roosts obviously weaken the tree right at the cavity height. Therefore, the exact hole location is a dangerous "pivot or snapping" point that can crush or injure animals in a cavity during a hurricane. Animals can also be trapped in downed cavities.

IBs do not nest in hurricane season; their fall roosts are likely less spacious than nests. However they seem to have been roosting in slightly smaller diameter tree boles.

|

| Cross Section Nest Diagram, Ivory-billed, courtesy USFWS |

|

| LA, NBP |

In Puerto Rico two hurricanes in September 2017 greatly reduced the islands namesake, wild parrot population. Some birds that were radio-tagged showed the immediate devastation Category (Cat) 4 hurricanes can do to cavity-nesters, like the Ivory-billed. It killed 17 of 20 parrots wearing tracking devices. “They found them dead under fallen trees and tree branches,” per researchers.

The 3 separate groups of wild parrots had their populations reduced as follows:

2 birds left of 56 (3.5% survivorship)

4 birds left of 31 (12.9 % survivorship) and

75 birds left of 134 (56% survivorship).

Well over half the birds were killed by these two hurricanes.

The habitat was so impaired by the hurricanes that captive birds could not be released due to continuing reduction in range quality and carrying capacity.

The 2020 LA hurricanes did not cause the level of leaf stripping and tree blow down rate as occurred in Puerto Rico (PR). Mortality rate of Ivory-bills is likely much less in LA than PR for these particular events. But of course there are many less IBs than Puerto Rican Parrots and every Ivory-billed at this point is genetically important.

Just as the 2017 PR hurricanes did, the 2020 LA hurricanes initially reduce the quality of habitat for birds, such as Ivory-bills. After these LA hurricanes there is likely a 20% decrease in standing dead wood with insects due to blowdowns. Favorite feeding areas for individual IBs is also initially altered or destroyed and birds have to learn and locate where replacement resources are. There is also an initial reduction of an estimated 10-80% in arboreal plant food resources (berries, nuts, etc.) due to blowdown and damage to the herbivory. A reduction in roosts and nest holes is another impact.

When the immediate storm impact is not fatal ecological conditions incrementally stress the remaining birds. There are lessened resources, increased exposure to the elements with a concomitant higher risk of injury or death by predators after storms. When resources are depleted the upcoming breeding phenology is affected. After several months resource levels have usually improved from the nadir; regardless the initial months after a hurricane are slightly to somewhat sub-optimal for survival and negatively impact breeding.

In September 1989 the Category 4 hurricane, Hugo, hit a well-studied, southeast US endangered woodpecker population of 1,765 birds. An estimated 700 Red-cockaded Woodpeckers survived the devastation in South Carolina. Eighty seven % of the active roost/nest trees were destroyed. These birds were in forestland that stretched from the coast to 30 miles inland.

Laura's hurricane wind speeds of Cat 4 to 1 reached well into the northern half of Louisiana.

Hurricanes have adversely impacted many interior forest species and large areas in the New World. Studies indicate the average intensity of hurricanes is increasing.

|

| Hurricane Laura, CAT 4 = Red, CAT 2 = Yellow, NBP |

Although many of the most severely imperiled species and events have occurred on islands, today's Ivory-billed population dynamics closely parallels island demographics. Small, widely segregated groups of one or a few IBs suffer the same threats as do reduced island populations. Small numbers of heterogeneously distributed and clumped mainland animals are very susceptible to the high winds, flying debris, cooler driving rains, resource depletion and habitat destruction that hurricanes inflict.

Here is an estimate of how many Ivory-bill Woodpeckers may have been injured or killed by only the one Cat 4 hurricane (Laura) that hit LA in 2020. The other four hurricanes/tropical storms that impacted Louisiana in 2020 have not been estimated for impact to IBs but were weaker and likely less severe events than the subject Cat 4 in relation to IB injury or death.

The severe record freeze of ~ 5 days in 2/2021 in LA, another random event, may have also caused IB fatalities.

Method Used to Deduce the Impact to Ivory-bills: Professional foresters in Louisiana produced an official estimate of dollar damage to trees based on aerial data and field measurements. The dollar damage was used with value of trees and salvage value to establish a workable number of trees damaged by the hurricane.

The impact area of the hurricane pertinent to tree damage was estimated at 15% of the states total area. Although high winds may have covered over more than 15% of the state this peripheral area was modeled to have negligible impact to tree value/damage and therefore IBs. The estimated number of trees damaged was used with the total number of trees in the impacted area to calculate a percentage of trees damaged in the impact area.

The percent of trees damaged was applied to three different hypothetical numbers of Ivory-bills in the impacted area. The 9.2% of trees damaged was used to assume 9.2% of occupied roosts were blown over, snapped or destroyed. This damage level (9.2%) seems much less than other Category 4 hurricanes but this is attributed to the well known condition that winds weaken as they move hundreds of miles inland. Laura's hurricane strength winds did eventually decrease to tropical storm levels but not until it approached the Arkansas line. Laura was a very destructive and "penetrating" storm for Ivory-billeds.

The Puerto Rican Parrots and Red-cockaded Woodpeckers roosts above that suffered much higher destruction rates were within 35 miles of the coast and close to the path of the respective Cat 4 hurricane.

An impacted tree containing a roosting IB was modeled to injure or kill the IB 90% of the time. Ivory-bills roosts by definition will weaken the structure of the tree right at the hole location, making it a potentially dangerous situation.

|

| Cavity Can be a Dangerous Place in a Hurricane, courtesy USFWS |

The hypothetical IB population numbers in the impacted area were 2 Ivory-bills, 6 Ivory-bills and 1,556 Ivory-bills, the latter representing a precolonial population number.

By using 2020 hypothetical IB numbers and comparing them against reasonable precolonial numbers we can examine the impacts of hurricanes and random events on a small population versus a large population of IBs.

Raw Data and Assumptions Used (see references)

8.9 Billion trees in Louisiana (LA)

Damage to forests/loss of revenue estimate is $ 1.1 B

Salvage rate ~ 75% of undamaged value

(note salvage value can be higher as commodity prices rise after hurricanes) If actual salvage higher, then the

number of trees downed/severely damaged increases and estimated fatality/injury rate of the Ivory-billed goes up proportionally)

Trees worth $35/tree undamaged

Damaged trees are in general harvested and still worth (.75 X 35) = $26.25/tree

Loss per damaged tree = ($35 - $26.25) = $ 8.75/ tree damaged

Number of trees in path damaged = $1.1 B loss of revenue/$8.75 = 125,000,000 trees lost or damaged

Estimate of path of damage as % of LA = 15% = Impact area

Estimate of total trees in path (15% area of LA X 8.9B trees LA) =1. 335 B trees

Percent of trees in path lost = 125,000,000/1.335 B trees = 9.2 % of trees destroyed

Estimate range of number of IBs in path = 2 or 6 or 1,556 birds

|

| On the Atchafalaya River, LA NBP |

IB occupied roosts destroyed/snapped/felled during hurricane

9.2% of 2 birds to 9.2% of 6 birds 9.2% of 1,556 birds

Assume 90% chance of injury or death if roost damaged during hurricane

2 birds in roosts in impact area = each had a 8.3 % chance of being injured or killed 16.6 % chance one bird injured or killed ~.7 % chance of both birds being injured or killed

6 birds in roosts in impact area = each had a 8.3 % chance of being injured or killed

~ 50% chance one bird injured or killed out of 6

~ 3.5 % chance two birds injured or killed out of 6

~ 1.2 % chance three birds injured or killed out of 6

~ .29% chance four birds injured or killed out of 6

~ .048% chance five birds injured or killed out of 6

< .000001% chance all 6 birds were injured or killed

Precolonial estimate of IBWO population and estimated fatality Cat 4 Hurricane circa 1600 AD

LA has 51.843 sq miles x 15% impact area = 7,776 sq miles

Using 10 sq miles/pair IBs = 778 pairs = 1556 birds

Per above 9.2 % of IB occupied roosts destroyed/snapped/felled during hurricane

Assume 90% chance of injury or death if roost damaged during hurricane. 9.2% x 90% x 1556 birds = 129 birds estimated to be injured or killed on average per Cat 4 hurricane

On average 8.3% of population injured or killed per Cat 4 hurricane circa 1600 AD

|

| Ivory-billed Roost Hole, LA, Tanner |

Summary: The area impacted, in relation to downed/damaged trees, by the subject hurricane was estimated at 15% of the state (LA).

Knowledge of private and public Ivory-billed reports recently and over the last 25 years was used to establish a range of Ivory-bill population numbers in the impacted area of 2 or 6 birds.

Higher numbers are possible but article reviewers proposing larger numbers based it on "large unsearched areas" with no data comparing large areas actually searched against unsearched.

There also was no presentation on the reduced carrying capacity of modern open spaces in the 15% area of LA addressed here; todays, young managed pine forests and remnant bottomland forests are likely not conducive to increasing IB numbers or perhaps even stable IB numbers.

Any higher number than 6 would infer that there are ~ 50 IBs in LA alone, other variables being equal. There is no evidence that there are many birds left in LA, let alone even 20 birds. However the hurricanes path did take it through some of the best areas of LA as far as a few recent IB reports; therefore it is reasonable to infer that the area impacted could have had a greater concentration of IBs than the remaining 85% of LA.

The impact area may have had 6 birds yet the total number of birds in LA can still be well under 50 birds or even 20. Two to six IBs in the impacted area seems to be a reasonable range of Ivory-billeds in the subject area at this time.

For a number of 2 birds in the impact area: This Category 4 Hurricane or a similar one can injure or kill 1 of the 2 birds in impact area 16.6% of the time for each Cat 4 hurricane. The probability of both birds being killed or injured is .7%.

For a number of 6 birds in the impact area: This Category 4 Hurricane or a similar one can kill or injure 1 of 6 birds in path area 50% of the time for each Cat 4 hurricane.

Average Decrease in Ivory-billed Numbers per Cat 4 hurricane

2 birds in area = 16.6% of the time for each hurricane there is a loss of 50% of the birds (1 bird).

2 birds in area = .7% of the time for each hurricane there is a loss of 100% of the birds (2 birds, all birds lost).

6 birds in area = 49% of the time for each hurricane there is a loss of 16% of the birds (1 bird lost)

6 birds in area = ~ 4% of the time for each hurricane there is a loss of 33% of the birds (2 birds lost)

1556 birds in area circa 1600 AD = on average 129 birds are injured or killed per each Cat 4 hurricane.

On average 8.3% of the precolonial population may have been injured or killed per Cat 4 hurricane.

For several weeks after any Cat 4 hurricane the survival rate is likely to be slightly lower than usual for the adults since standing dead wood with insects/food resources is initially decreased by ~ 18.4 % (standing dead wood is estimated to have twice the rate of blowdown as damage to roosting trees, 9.2% x 2 = 18.4%).

|

| NBP |

|

| LA, NBP |

Conclusions: Small populations of animals in the New World have been driven towards or into extinction by random events such as hurricanes. There are an unknown but very small number of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers left in the US.

Ivory-bills are in danger of accelerated or rapid extinction via common random events such as hurricanes, fires, disease, drought, shooting, genetic stochastics, etc. In addition to random events Ivory-bills suffer mortality from expected events such as predation, expected common diseases, old age, etc.

In 2020 five tropical storms and hurricanes hit the state of LA; one, Laura, was a powerful and destructive Category 4. This single random event alone may have injured or killed one Ivory-billed of the 2 to 6 estimated Ivory-bills that remained in the impacted area of LA.

Although a portion of the Ivory-billed's total population have been hit with hurricanes throughout their existence, large, healthy populations of animals were present in ~ 12 states in precolonial times; recuperation from hurricanes was normal. Only a fraction to a smaller portion of all existing IBs were injured or killed by random events each year. The much larger population then, with a vast range of tens of millions of acres, had a healthy contiguous forest with various areas of concentrated dead trees (hurricanes, large forest fires, insect outbreaks, tornadoes, beavers, etc.) and they could successfully fledge many birds in the post hurricane years.

Today's younger, lower quality, fragmented, mostly narrow linear forests, with limited standing dead wood and decreased peak insect biomass are not able to fledge as many birds per existing IB pair.

The presentation in this article portrayed that one Cat 4 hurricane can reduce a starting number of 2 Ivory-bills to and average of 1.6 birds. Five such random events can reduce the number to an average of .79 birds. When numbers drop below 2 functional extinction is predicted

in that immediate area. A single bird, will have to move and search for a suitable unrelated mate. There is some evidence that females may not disperse far from their natal area. Birds are now very rare; a lone bird may not find a mate.

CHART : Collates Starting Number of Birds with Average Number of Birds Expected to Survive 1, 5 and 10 Random Events

Inevitably there will be a series of random events that hand each remaining pocket of Ivory-bills a final blow.

Basic habitat management may be able to increase the numbers of Ivory-bills which would help stave off extinction.

Footnote

* Stochastic genetic effects for small populations- definitions/explanations - Each animal in a small population may have genes and traits that are possessed by few or no other living animal within that small population. If this or these animals are lost before they successfully have offspring those unique genes and beneficial traits are lost forever to all future animals and the entire population.

If, for example, the gene was carrying the coding or tendency for characteristics such as the ability to better fight off disease x and z or to lay 5 eggs instead of 4 the possibility of being more resistant to disease x and z, or to lay 5 eggs instead of 4, is now lost or reduced for all future animals for that species.

This is called genetic loss via genetic drift and results in single animals and the entire small population having less viability and survivability.

Small populations are mathematically more likely to suffer rapid genetic loss and drift than larger populations.

Another stochastic genetic effect that impacts small populations is inbreeding. A gene consists of two alleles, one from the female parent's egg and one from male parent's sperm. Some alleles are deleterious to the animal but are recessive meaning that any other type of allele within that gene will mask or eliminate the deleterious effects of that one "bad" allele. However if both alleles (one from female, one from male) are the deleterious allele the animal genome will express and the animal will suffer from the ramifications of this "bad" gene.

If, for example, the non-deleterious gene was to carry the coding or tendency for characteristics to produce an enzyme that best digests acorns or the ability to see the color red, the possibility of the bird being better able to digest acorns or quickly recognize predators or mates that have red colors is now lost or reduced for that particular animal. If this hypothetical animal successfully reproduces it will by definition only be able to pass on these deleterious alleles for that respective gene.

Inbreeding results in single animals and the entire small population having less viability and survivability.

Small populations are mathematically more likely to suffer rapid inbreeding than larger populations.

Many thanks to Zoologist Frederick Virrazzi for this and other articles.

References and Bibliography

Out

My Backdoor: Hurricanes Can Affect Backyard Birds | Department

Of Natural Resources Division (georgiawildlife.com)

AgCenter estimates ag, forestry losses

from Hurricane Laura exceed $1.6 billion (lsuagcenter.com)

2020 Louisiana Hurricane season recap

(ksla.com)

https://www.netstate.com/states/tables/st_size.htm

Hurricane LAURA Rakes Sulphur,

Louisiana (2020) - Bing video

VZ_154_Last_St_Kitts_Bullfinch.pdf

(si.edu)

(PDF) Grand Bahama's Brown-headed

Nuthatch: A Distinct and Endangered Species (researchgate.net)

Hurricane Hugo - Wikipedia

Bahama Nuthatch – birdfinding.info

Miami blue butterfly (biologicaldiversity.org)

Impact of Hurricane Hugo on Bird Populations on St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands on JSTOR

SAVING THE MIAMI BLUE BUTTERFLY

After Hurricane Andrew ripped through South Florida in 1992, the already-scarce Miami blue butterfly almost went extinct: No one recorded a single sighting for years. Finally, in 1999, a cheer went up among butterfly enthusiasts when a photographer discovered 35 specimens in Bahia Honda State Park, which then housed the only wild population of Miami blues — but from which all known butterflies once again disappeared in 2010. This leaves only a few scattered individuals in another population in the Marquesas Keys in Key West National Wildlife Refuge. Despite captive-breeding and reintroduction efforts, this sun-loving coastal butterfly, once common throughout South Florida, is now one of the rarest insect species in North America.

The Miami blue experienced its first major setbacks in the 1980s, when coastal development exploded and Florida's war on mosquitoes dispersed toxic chemicals throughout the butterfly's range. In 1984 the butterfly became a candidate for federal listing. Owing to the efforts of the North American Butterfly Association, the species was declared endangered in the state of Florida in 2003. And due to a landmark 2011 agreement with the Center to push 757 species toward protection, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has put the butterfly on the endangered species list.

But that protection was hard-won: In reluctant acknowledgment of the Miami blue's severe population decline and increasing harm from known threats, the Service proposed — but didn't finalize — emergency listing several times between 2000 and 2004. In 2001, the Service came to an agreement with the Center and other groups to expedite protection of 29 species, including the Miami blue, under the Act. But instead of granting the butterfly its rightful endangered status, the agency declared in 2005 that while the butterfly did merit protection, lack of funding prevented measures from being taken — and the species was again deemed a “candidate” and condemned to the “warranted but precluded” list. The Center challenged this determination with a notice of intent to sue in the same year, and we also filed suit to earn prompt protections for every one of the hundreds of species on the candidate list. When the butterfly was discovered missing from Bahia Honda State Park, in 2011 we filed an emergency petition to list the butterfly as endangered — and filed another notice of intent to sue when that petition was denied.

Many thanks to Zoologist Frederick Virrazzi for this and other articles.

RAW DATA, comments and info from this point on may be copyrighted to others sources than NBP. Below will be organized or deleted in final draft.

In the Bahamas, the woodpecker is common on Abaco, rare on San Salvador Island, and thought to be extirpated on Grand Bahama. A pair seen recently on the east end of Grand Bahama (2002-2004) may be good news for the Grand Bahama form but more likely represents a colonizing pair from Abaco. Unfortunately, these birds have not been seen again since the hurricanes in September 2004

Distribution of West Indian Woodpecker (Melanerpes superciliaris). The three Bahamian subspecies live on Grand Bahama (M. s. bahamensis), Abaco (M. s. blakei), and San Salvador Island (M. s. nyeanus). Three other forms (from north to south) live on Cuba (M. s. superciliaris), Isle of Pines (M. s. murceus), and Grand Cayman Island (M. s. caymanensis). Several additional subspecies have been described from isolated islands off Cuba (not shown here). Map: William K. Hayes.

After hurricanes with >160 kph winds passed over San Salvador, woodpecker densities declined to 35–40% of pre-hurricane densities, but generally recovered back to pre-hurricane densities within 2–3 years. Based on an estimated density of woodpeckers within a ~1,400 ha occupied area, we calculated a population size of approximately 240 individuals (CI = 68-408). However, the population declined to far lower numbers immediately following hurricanes.

High Winds

Laura's eyewall produced extreme wind gusts in Louisiana and southeast Texas:

-Lake Charles, Louisiana: 133 mph

-Calcasieu Pass, Louisiana: 127 mph

-Cameron, Louisiana: 116 mph

-Sabine Pass, Texas: 89 mph

-Alexandria, Louisiana: 86 mph (video from Mike Seidel)

Storm chaser Mike Theiss measured a peak wind gust of 154 mph in the western eyewall of Laura near Holly Beach, Louisiana.

NBP notes = Starting # Birds Average # Birds after 1 Random Event Average # Birds after 5 Random Events Average # Birds after 10 Random Events 2 1 (16.6% chance) 2 (83.4 % chance) average 1.66 birds 0-1 (62.2% of time) 2 (37.2% of time) average .79 birds 0-1 (84% chance) 2 (16% chance) average .3 birds 6 5 (51% chance) 6 (49% chance) average 4.98 birds average # of birds 2.4 birds average # of birds .93 birds 1556 1427 birds 677 birds 266 birds

See our other article on Ivory-bill reports from South Carolina, by using this link of return to the Home page.

|

| Congaree River, SC NBP |

|

| LA NBP |