Evidence and Video Review of the SE Louisiana, Ivory-billed Woodpecker (2008)

Fred Virrazzi, ZoologistAbstract

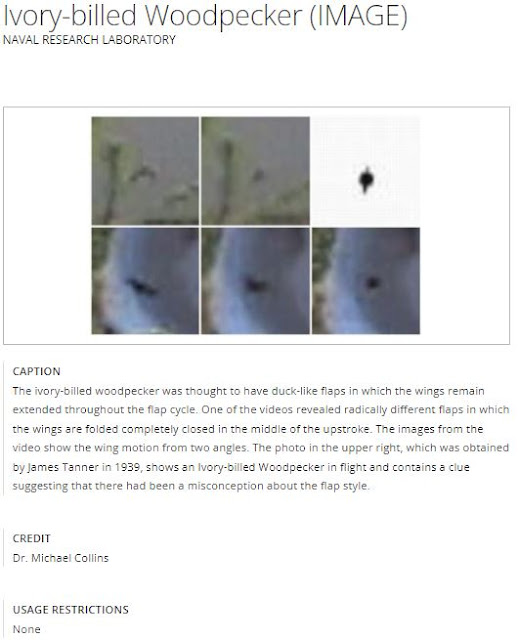

Despite the publication of peer reviewed papers on the evidence of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker, Campephilus principalis, in the Pearl River basin in 2008 (video; multiple peer reviewed papers, M. Collins) the USFWS and others decided to dismiss this pertinent 2008 information without serious scientific inspection.

Here an independent examination of the subject video and papers' assertions was conducted while again asking the public for suggestions on what species was in the video. All mentioned confusing species were listed, discussed and considered including unusual species such as the Ringed Kingfisher (rare, extralimital). The ~ 400 pertinent frames of the video were examined with the intent to find the possible common to rare species in the video. The audio was reviewed, and the only species heard that could also be the subject of the video was the clear double knock of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker at :16 of the raw 8.mov file (see link to download).

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker had all 20 attributes seen in the video/papers while all other species averaged ~ 5 attributes with a maximum of 8 for two of the eight species. Because of the singular and more so the collective specificity of the attributes, the characteristics matrix completely eliminated all species as being in the 2008 video but an Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

Background

Here is one of Collins' papers: Collin paper

The Pileated Woodpecker's conspicuous wing binding in level flight is well known; this bird does not visually show any or that extent of wing binding. But as B. Tobalske, ornithologist known for his bird flight dynamics research, and any viewer watches the slowed video the wing binding is easily found left of the "perch tree" starting at 1 min 33.5 secs of your downloaded 2008p.mov by slowly advancing the frames (link to download below). Very few large, SE USA birds bind their wings, one being the Ivory-billed according to at least one Singer Tract photo and the subject video. The Ivory-billed's closest relative also shows wing-binding, see the only films of the Imperial Woodpecker (2010).

Here the assertions on the above kinematics and characteristics with a comparative look at the bird's plumage.

|

| Frame of video showing a fast flying bird with characteristics of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker flying towards two o'clock at ~ 135 degree sight line. This frame is soon after the 3 frame sketch below. |

|

| Picture of English Bayou Showing Dark Substrate , credit Collins |

|

| Dr. Lowery on short flights of the IBWO and the superior plumage view at that time |

|

| new |

Ecology

Why was an Ivory-bill in the Pearl River in 2008? The Pearl River basin was dotted with some of the largest logging camps in the world especially after the railroad reached the area circa 1855. The heavy logging continued into the early 20th century. Tanner (1942) declared the area completely cut over during his visits in the 1930s. Prior to the logging there were certainly Ivory-bills there. During the logging the human population expanded; they needed buildings and to eat : "They had venison and wild game in abundance." Some IBs may have been shot for target practice, out of curiosity or for food.

Since the Pearl basin was one of the earliest, heavily logged, and hunted areas in the subject states, Ivory-bills were effectively gone from the area by the 1930s. Concomitantly the area was one of the first to regenerate mid seral forests that could support a few Ivory-bills by the late 20th century or earlier.

The river has had Ivory-bill sightings for decades; a lengthy, 10 minute, close sighting of a pair in 1999 by D. Kulivan, a turkey-hunter and LSU student, is considered by many as the genesis of the modern C. principalis era. This witness and his report were fully vetted by Louisianan ornithologists; it was said to be the most convincing Ivory-bill report in decades.

Pearl River Reports noted in the USFWS 2010 Recovery Plan (per C. Hunter) are as follows, with an NBP 2012 report added and others :

(E-2) Pearl River, St. Tammany Parish, LA (a male observed one year, a female the following year, both by N. Higginbotham); 1986, 1987 (Steinberg 2008) 1990-1999 (E-2) Pearl River, St. Tammany Parish, LA (a pair reported seen for 10 minutes by D. Kulivan while turkey hunting; extensive follow up searches in subsequent years unsuccessful); April 1999 (Jackson 2004) 2000-

2002 Pearl River, LA - M. Collins in a Bird Forum post of 2/2/2006 said "A field biologist who works for NASA saw an ivorybill here in 2002. The birds were also seen or heard by others."

(E-2) Pearl River WMA – Stennis

Space Center, St. Tammany

Parish, LA, Hancock County,

MS (multiple sightings, several

very poor but at least one

suggestive video in 2006 of a large

woodpecker, possibly lacking

red in the crest; a more recent

video of a woodpecker in flight

in 2009 was determined to be a

Red-headed woodpecker, a 2008

video is still undergoing review

by M. Collins and others); 2000,

2005-2009 (USFWS 2007; Collins

2005-2009)

Lower Mississippi Delta (#’s

2012 Pearl River WMA, English Bayou (same exact bayou where the 2008 video was taken). On November 24, 2012 Matthew Dell watched a large all black and white woodpecker (no red) with trailing white wing area, approach his position and land with a substantial sweep up on a Sycamore tree. The bird was "well within 50 feet at the closest point"; he saw the "head and neck" particularly well. Dell is (2022) a retired Chief Deputy US Marshal.

Adding to those sightings forwarded to USFWS personnel in two manners on 7/21/22 is the following text: In 2012 NBP received a report from F. Wiley that an Ivory-bill had been seen ~ 4.5 miles SW of the 2008 woodpecker video location, on the Old Pearl River. We interviewed the viewer on video (unpublished); he provided sketches and was very convincing that one Ivory-bill had passed through this wooded residential area on the west edge of the Pearl swamp forest twice in 2012. The bird was foraging but upon detection of the viewer took off.

We headed east into the forest for over one mile in a cut, camped, searched and did acoustical point surveys in the area for two days and found the interior river forest subpar but very secluded; it was impenetrable due to deep mud in all directions. There were many cottonmouths in the few locations we penetrated more than 50 feet into the forest interior. No detections or sign were had. The larger trees in the area were actually in the well treed residential tongue; dominant were oaks, pines and along water, cypress. The bird may have been exploring the edges of the Pearl bottomland and found a few feeding trees while cutting through several residences, in its path, briefly that year.

The location where the 2008 Ivory-billed was videoed is the widest section of the secluded basin (5 mile width there, less elsewhere). Collins is not an ecologist; he was unaware of National Biodiversity Parks's various Ivory-billed habitat occupancy models (NBP, unpublished). These models were, at the time, developed without any Pearl data but when applied to the Pearl basin it designated the IBWO, 2008 location in the top 5 % of square miles in the ecosystem for expected usage. All of the several different Ivory-bills that National Biodiversity Park's teams have located form an ecological pattern for occupancy. The basin has some input of dead wood due to storms, hurricanes and saltwater intrusion from risings sea levels.

Video Details

Yes, most of the frames are low resolution but quality does vary. There is plenty of evidence in the video of the subject's characteristics, morphology and kinematics. Nothing in the cormorant, heron, ibis, duck, shorebird or hawk families has even a few of the empirical characteristics or plumage details showing in the "flyunder" video.

Throughout the video there is reflections (mirror image) of the bird on the surface of the water; this has also provided information. Reflections are not shadows so will have an image of the subject bird. These provide some surprising evidence to the careful reviewer; some are presented here. Many frames are not showing much of the bird, but the initial frames were used to establish wing beat Hz by Collins and B. Tobalske. In several frames the entire dorsal surface of the wings and midbody are shown but resolution is poor. In dozens of frames parts of the white on the dorsal surface of the wings and midbody are shown. The position of the white in the wing, when seen, is constantly on the back half of the wing with no trailing black edge.

Black in the dorsal wing is limited to only the front 1/3 to 1/2 of wing and the tips.

The head and neck are only seen in a handful of frames. The possible bill may be viewable in at least three or four frames.

Analysis (processing, averaging, etc.) could indicate the length of the neck/bill area even in this video further eliminating (again) many species by this alone. But the bill length is not needed since the careful analysis of all evidence and video shows the bird is an Ivory-billed.

Directions of How to Review the Video with this Paper

1) download data base (upper right hand corner) large zipfile and then open 2008p.mov file with the video (it is 1 minute 47.974 seconds long ) :

same link

Ivory-billed Woodpecker video https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.8w9ghx3hp

2) a bird double knocks ~ 16 secs into the 1:48 long movie (Ivory-bills double knock and double knocks are almost non- existent in the field unless an IBWO is involved in NBP's experience over many years in hundreds of square miles).

3) These 4 sequences of ~ 4 frames each are very important to seeing the Ivory-billed. Look for these clips and stills below which are being uploaded here. Or see them yourself via direct download.

After download you can extract the sequences, slow the speed, and crop, then save files or just play them on your screen. Zoom may not be available on free apps already installed on your PC. Without crop and or zoom it's hard to see the bird and its plumage.

|

| Brief Diagram of Some Key Sequences |

sequence 1

All these features are there (the bill is possible). Best to toggle back on the frames or loop videos.

|

| Soon after passing the perch tree the bird is reacquired heading towards 1 o'clock. In the video it can be viewed under the center, forked, branch that is close to Collins, ~ 110 feet away. As the bird passes the branch it is then viewed tip to tip. Suddenly it makes an ~ 45 degree turn to the right as it points its right wing way down in relation to the left as an aerodynamic brake to produce the desired turn. At this moment the bird is moving relatively slow as the angular velocity is suddenly centered on a vertical axis through the right wing. The right wing is moving much slower than the left. We get excellent evidence of the right wings leading black and trailing white "half wings" and long aspect ratio. We also see the dorsal stripes of an IBWO. And the left wing at the raised angle causing foreshortening, quite different than the right wing angle. |

|

| Soon after passing the perch tree the bird is reacquired heading towards 1 o'clock. In the video it can be viewed under the center, forked, branch that is close to Collins, ~ 110 feet away. As the bird passes the branch it is then viewed tip to tip. Suddenly it makes an ~ 45 degree turn to the right as it points its right wing way down in relation to the left as an aerodynamic brake to produce the desired turn. At this moment the bird is moving relatively slow as the angular velocity is suddenly centered on a vertical axis through the right wing. The right wing is moving much slower than the left. We get excellent evidence of the right wings leading black and trailing white "half wings" and long aspect ratio. We also see the dorsal stripes of an IBWO. And the left wing at the raised angle causing foreshortening, quite different than the right wing angle. |

1:39 583 to 139 716

|

| Frame 1:39.516, the same frame as the middle frame in 3 frame sketch above. This was an early version based on a poorly extracted frame, of lower quality than was eventually extracted. Regardless the Campephilus W pattern is plainly shown. This shows the loss of details if you are not properly extracting this video. |

|

| Frame 1:39.499, small image of bird in center dark, to the right of whitish-green branch, flying towards 2 o'clock |

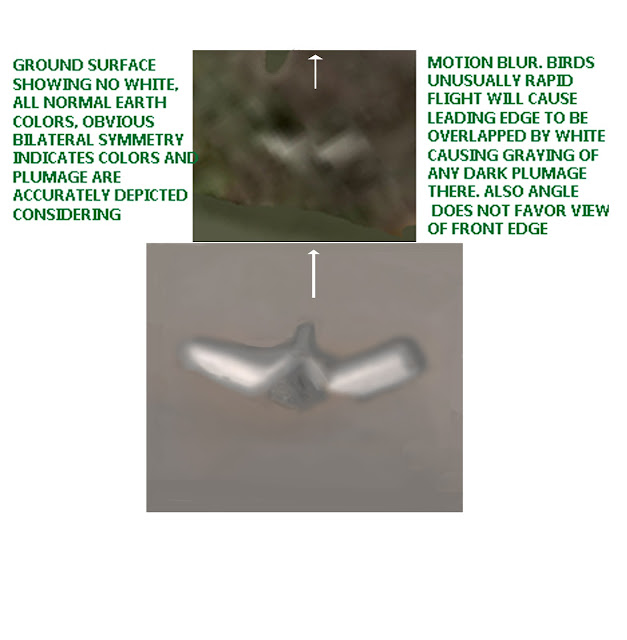

4) Black in front half of wing --- Evidence of a black leading half of the wings is hard to observe since only the right side of the perch tree is the angle of sight advantageous to see that part of a flying bird. But even on the right side the angle of sight is ~ 140 degrees and far from being ideally right above (90 degrees). Also, the white in the leading edge of the white wing area is being "dragged" over the front half of the dark wing area due to typical directional motion blur masking part of the IBWO's black.

The right side of the tree also has the dark background of the bayou mud assimilating the black; it's also an overcast day. Despite these impediments the black is seen in multiple consecutive frames in the short video sequences above and in frames on both sides of the tree.

It is my assessment that the ground/bird is slightly overexposed and if possible, a slight darkening of the video can improve sequence 1, etc. from raw but that does not necessarily help resolve the black in the wing, just the opposite. Different parts of the wing at opposite end of the light spectrum, white vs. black, may require different video settings to deduce or see their actual "colors". The same sequence can be more accurately examined as far as true appearance, by comparing different video iterations. Any careful examination of this article with the raw download will lead to seeing this bird's wings match perfectly, considering quality, an Ivory-bill's dorsal wing pattern, shape and kinematics

Flight sequences rather than some stills are better to show the critical black in the leading half of the wings; the conspicuous white in wings is seen in frames or sequences. Wing color is also more noticeable in some sequences as the flying bird suddenly blocks the mottled lighter brown and dark green ground/mud/foliage background and then the moving solid black "patch" in the wings is more easily noticed in those frames. When you see the black in the wings in any video sequences you extract you are processing the video right (download, slow-mo and zoom).

When you get this sequence properly prepared and see that 3D effect and black wing batches, you have the speed, light contrast, sharpness, gamma, zoom and quality RIGHT. The desired sequence is represented here with several versions. The superior sequences in this article will mainly be in the beginning of the article.

|

| Three Consecutive Frames (Note dark substrate must not be confused with wing areas via observer bias), but white is mostly real except for minimal area caused by wing blur, note angle of middle bird trailing white edge shows upstroke occurring; and long tapered angle of wing, notice how white is fairly consistent in frames according to obvious kinematics, note in the middle frame the wing tip to wing tip whitish "W" also seen in some frames of AR 2004 IBWO, and in some clear to blurry frames of some Campephilus but not in Pileateds. This "W" is a known field mark for some Campephilus species, certainly something to check, black leading edge is there but more easily seen in videos, see suggestion of white extending into neck in all frames, especially middle, note that if it's incorrectly suggested there is no, wider than perceived leading black area, we are confronted with explaining what large species has long, slim, all white wings like this except some Laridae, Ardeidae and Anatidae (gulls, herons, ducks); since it is not any of those it is very likely this bird has at least a bicolored wing, presently with some part of the leading half of wing chord not easily resolved when a dark substrate is involved (most likely unseen leading wing area is black, brown, or maybe dark green). add--Careful examination of videos now confirms substantial black in front half of wings in key frames of Seq 1. The 2004 Arkansas IBWO video should also be looked at to see similarities or inconsistencies between these two videos. Here is an enhanced AR video: |

|

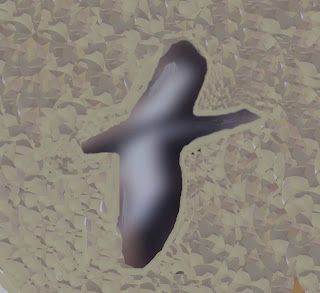

| Here is an Ivory-billed picture, blurred, with part of tail lost to roughly approxiamte conditions in the 2008 video |

Evidence Review List of Plumage/Characteristics

Wing Beat Frequency

Flight Speed

Wing Binding

Aspect Ratio

Synchronous Molt

Ventral Bird

Dorsal Bird White Trailing Half of Wings

Dorsal Bird Black Leading Edge of Wing

Dorsal Bird White"W" Pattern

An ~ 12 frame video sequence here, same frames as a video above but gamma increased. Note the obvious black in front half of moving wings, very little noticeable wing binding, and more. No frames show any "confusing species". See here:

Wing Beat Frequency

The original papers' wing beat frequency was confirmed here by counting and timing wing beat frequency, frame by frame, using XXXXX software. The video was slowed to 10% speed for two "long" sequences visible in the first half of video on the left side of the perch tree. The bird has a wing beat frequency in level flight of ~ 8.5 Hz/s.

The birds wing beat Hz and speed is much higher than any PIWO ever "found" (level flight). Speed of bird was calculated to be ~ 34 mph. No PIWO examined by various authors, researchers or on any of the various large video collections shows the high wing beat Hz of this bird (or the Luneau 2004 AR IBWO, or Imperial Woodpecker 1956). The sample size for the PIWO videos is N = 25. SD (standard deviations or range) of wing beat Hz has been found to be only a fraction (~10%) of the Hz in the Picidae and almost all species of birds. For example, PIWO is ~ 5/s and the range is 4.5/s to 5.5/s.

IBWO (Luneau 8.8) and IMWO (8.1) and other putative IBWO data is > 8.3 beats per second. A PIWO cannot likely physically flap this fast in sustained flight without causing muscle/joint injury or the maximum speed potential is reached prior to obtaining that rate.

The bird in the video cannot be a PIWO from just this one characteristic alone. And since there's been numerous erroneous proclamations in the past that the bird is a normal to leucistic PIWO this eliminates all PIWO's since plumage variation/abnormalities in PIWO does not mysteriously increase wing beat Hz.

Some of the original methods that skeptics escaped carefully examining, or even considering, wing beat Hz in basically level flight of the 2004 AR and 2008 LA video, are still to:

a) refuse to discuss the issue (ignoring scientific discussion does not mean extinction has occurred)

b) refuse to resolve the rate by letting occasionally occluded views of two frames negate the ability to do simple extrapolation of the wing cycle (this was claimed by the 2005 skeptics constantly)

c) say that "birds fly in different ways" (true, but level flight of hundreds of species shows a small standard deviation and PIWO does not overlap IBWO Hz in level flight)

d) birds are not IDed by flap rate (untrue most good trip leaders, field researchers, etc. use flap rate sometimes to gauge what species they are seeing, even at distances of up to a mile)

If we look at plumage and other features, they also eliminate a PIWO of any plumage as being in the video.

|

| SD of wing beat Hz is low in birds. Here is only a very small number of species that have data. Many species have empirical data including PIWO and now IBWO, no overlap at all in these two. This video has a bird with a Hz of 8.4 |

A new preprint paper has half a million wing rotations measured for various species; it again confirms the small intraspecific standard deviations for wing beat frequencies of birds. The literature is clear on the small standard deviations of avian wing beat Hz across taxa including Picidae.

The role of wingbeat frequency and amplitude in flight power (biorxiv.org)

This recent paper might contain more bird species than any single study in a field getting more and more attention. Since aerodynamics has significant applications in design, transportation, aviation, space exploration, military, etc., this may explain the increasing research.

For this 2008 video, the first half of the video (easier, more open canopied half) was used. Two people did the counting and timing. There are a few branches but the rotation per wing beat in degrees from prior visible frames made it possible to know where you are when a frame or two is occluded. Analyses of 1.5 seconds and ~ 1sec on left side of tree was done. Our results were very similar to Collins' published papers for Hz.

This is a very high wing beat frequency which can be expected if you look at any of the formulas. A bird this large with only a marginally greater wing surface area than a pileated yet much heavier and much faster, must have a higher wing beat Hz.

This bird agrees with the three other known wing beat frequencies for the two Northern Campephilus species. It's much higher than PIWO. This is 4 or 5 SD from PIWO. 3 SD covers 99.7% of measurements in randomly distributed data sets. Wing beats are not a normally distributed data set so the range of values is constrained via aerodynamics, physiology, etc. The SD should be smaller.

The Hz was checked against the audio provided; no speed up of the video was detected. The species singing during the woodpecker's flight are exactly the same community of species singing in the prior 1:30. The avian species and songs agree with the late Match date. An insect is seen and heard on the video; good. This is done only as standard verification exasperated by a "skeptic" inferring that the video had been sped up. Obviously, there is enough understanding and trepidation about wing beat Hz implications by some skeptics; that is telling.

Flight Speed

Throughout the literature, from A for Audubon, on to much later letters in the alphabet, many observers have said the Ivory-billed flies directly and rapidly "much like a pintail duck". PIWO of course have been said to be, and are, much slower and with noticeable wing binding. The video bird's wing beat Hz and speed is much higher than any PIWO ever "found" (level flight).

Speed of the bird was calculated to be ~ 34 mph (Collins). In this examination we estimated that via gross measurements that the bird is flying at ~ 33 mph, this is an estimate however since we did not have exact distances from point to point. Regardless No PIWO examined by various authors, researchers or on any of the various large video collections shows the high wing beat Hz of this bird (or the Luneau 2004 AR IBWO, or Imperial Woodpecker, 1956) or speeds over 25 mph.

Wing Binding

The author confirmed the subject bird has wing binding on most strokes by examing the frames on the left side of the perch tree at 10% speed. The time of binding per cycle was less than Pileated Woodpeckers observed by the author.

"A decline in the ability to engage in intermittent bounds is apparent with increasing body mass among woodpeckers (Picidae; Tobalske, 1995). "

Wing binding was found for this bird by an expert in flight dynamics. As I went through the first half of the bird's appearance, the binding is observed but it is not as pronounced as what a PIWO would show (binding for at least 4 frames or .067 s). Binding is empirically less than Pileateds. Only 3 large species are known or now suspected to bring their wings in close to body (binding) during level flight. Belted Kingfisher, Pileated Woodpecker and likely Ivory-billed Woodpeckers bind their wings.

In Collins' papers the following pertinent finding may not be mentioned. "A decline in the ability to engage in intermittent bounds is apparent with increasing body mass among woodpeckers (Picidae; Tobalske, 1995). " This inverse mass to binding relationship also supports that the 2008 video depicts an Ivory-billed. IBWOs weigh ~ 75% more than a PIWO.

|

| Here is a Pileated Woodpcker wing tip graph adjusted by the author to the scale of the IBWO in Collins insert above. This is 0 to 400 ms |

"Aspect Ratio"

The videoed bird has a very long and narrow wing that influences the aspect ratio. Both dorsal and ventral side of the bird's image show this despite the angle of view foreshortening the aspect ratio.

A simplified way of presenting the aspect ration is used here rather than the accepted definition. Here the wingspan is just divided by the average wing chord to derive the "aspect ratio". Raw data was gathered by measuring the respective bird components from various frames. Pileated aspect ratios were measured from pictures. Video frames will minimize the aspect ratio since foreshortening reduces the wingspan. Regardless the PIWO is expected to have a shorter ratio:

Video (unadjusted for foreshortening)

5.0

5.3

5.4

IBWO from Singer Tract (negligible foreshortening)

5.3

PIWO

4.0

3.9

4.0

The aspect ratio of a measured IBWO is 5.3 while the video measured average is at least 5.2. The PIWO measured average is 4.0.

Thís alone eliminates several possible species, noteworthy the Pileated Woodpecker. The PIWO cannot be the bird in the video.

The video bird was measured via subsequent field work with assistance from LDWS, others, to be 30" wingspan, while a Pileated Woodpecker is 29" and Belted Kingfisher mean ~ 22"

Synchronous Molt (NEW EVIDENCE 8/2/22)

In the second video sequence of this article, other sequences and frames in the original .mov file, a missing primary in each wing can be noticed at appropriate times during the flap cycle. While looping sequence video 2 (from start of article) a synchronous molt of Primary 1 can be studied as the bird flies on the right side of the perch tree.

Upon examination of over 200 IBWO specimens J. Jackson found that molt starts soon after nesting season for adults with Primary 1, progressing in sequence to P10 into the fall. This bird was videoed on March 29 and is alone indicating the nest season is likely over, or was skipped, for this individual.

It also may be an immature which was found to molt P1 at a similar time as adults. Since immatures have no breeding season and one was found by Jackson to have 5 new primaries by mid-summer it is likely that immatures start their molt on average a bit earlier than adults. The stage of molt sequence seen in this video is completely consistent with the specific, published literature for Campephilus principalis.

Here is an exert from J. Jackson, 2002

The plumage molt detail described here shows the resolution of the subject video is acceptable for fine details and therefore species identification logically follows.

Ventral Bird

An IBWO has a mostly white underwing with a black center bar flaring out distally as it approaches the tip, that divides the white wing "halves". The ventral bird also has a black body. Thís video has a reflection (mirror image) of the bird on the water surface and realtive colors or shades can be seen; it was a windless day and the water surface was flat. Many frames show the reflection, and they were examined. Here are some:

|

| Frame capture shows a black center line on each wing, surrounded by lighter gray area around all of the inner wing, while showing the expected darker center body area. Other reflection captures, brighter than this, also show black wing tips, this dark center line and dark body area where it is expected. Also details that are very nuanced with black wing tips points out that the reflection is showing actual fine plumage details (see above sketch). Any doubter must bring up these frames and extract and/or zoom images to see for themselves. These details are not easily seen except on your own PC screen. See other frames here. |

|

| Underwing reflection, bird heading towards 2 o'clock. Note darker body, lighter "left" wing much lighter than body, consistent with IBWO. Both wings have a suggestion of dark central bar when zoomed. Suggestion of long aspect ratio. |

Top sketch is of actual frame above of ventral side in video. Other sketches are what the respective species should look like in a video. Which expected species sketch matches the video? The best reflection frames all strongly or even exclusively favor the same species, IBWO. Statistically this is hard to explain away, over and over, in this video for characteristic after characteristic.

Examination of the ventral side of this bird supports that it is an IBWO.

Dorsal Bird White Trailing Half of Wings

This characteristic is seen in many featured video sequences and frames; it is considered the major field mark for an Ivory-billed followed by other field marks. The species and this bird have white primaries and secondaries across the entire trailing half of the wings.

The main field mark in the video is the major field mark of the IBWO. None of the other eight possible species has this field mark.

Dorsal Bird, Black Leading Edge of Wing

This is also a field mark, historically less than major, and not always seen well in flight over the centuries with reasons pertinent here. There are several frames that one can see the black but only a few frames that show its significant extent in the front half of the wings.

Not coincidentally the black shows best in frames on an upstroke or wing bend when the left inner wing is more perpendicular to the camera lens. And related some of the right forewing can show black on the downstroke when that plane of that part of the wing is more perpendicular to the camera lens. These nuances are strong kinematic evidence that the black is there.

The black is unequivocally seen in the latter half of sequence 1:39.483 to 1:39.600 and in subsequent frames. Looping these frames captures the often "fugitive" black.

The leading edge of a black wing should in fact be periodically masked and in that odd respect, it supports the hypothesis that the bird has a dark leading wing edge. The black is at a worse angle of camera acquisition than for the white, motion blur is pulling the leading edge of the white over the trailing part of the black wing and there is a dark background under the wing. As expected of any camera the black is hard to resolve due to these conditions. And as expected it is seen when conditions abate a bit for one or more of these factors.

The leading black's existence, even in frames it does not appear, is inferred by the unnaturally thin white in the wing mantle suggesting a gull or tern if that was the entire wing. Also, the leading white "edge" joins the body too far back positionally to actual be the leading edge and retain aerodynamic shape and function. There is something "missing" and when you see the black wing area during a video sequence it then makes sense.

Dorsal Bird White"W" Pattern

Some Campephilus including IBWOs; show a white W pattern on the dorsal side. This bird shows the W in a few of the best frames. This is an unusual field mark, a bit complex with several angles, making it distinguishable since it does not readily occur randomly in poorly resolved videos. For it to appear in a video gives good clues on what the species is. See later section in this article on a comparative species model using the "W".

|

| W pattern obvious |

Link to Original Paper LA 2008 Ivory-billed paper

First Video regular speed, 2nd video 10% speed.

|

| Old Pearl River South of I 10, the habitat is below average and impossible to survey efficiently due to endless mud. An IBWO was reported right here 9 years ago coming into a bordering backyard. |

SPECIFIC FRAME TO THE RIGHT OF MAIN TREE, SEQUENCE 1:39 .183 TO 1:39 .249

This next frame is at the end of one of the sequences highlighted above. It has lost resolution in the steps to get it into the article and more processing work is needed. The ~ 4 frame sequence is unique; there is an S shaped turn in a very short distance that gives good evidence on the birds ID.

This sequence will appear here and will be analyzed. The sequence is completely consistent with the bird being only one species, an IBWO. Any serious reviewer should look at the 4 sequences.

|

| This frame does not seem to be highlighted by Collins, but his works are spread out. He may have not noticed what appears in this frame, not sure. But it seems to have many field marks of an IBWO. They are poorly resolved however, but they may all be there. Background must be checked for 2. Tail. I feel tail is not lined up correctly with axis of bird, plus other reservations. This frame is supporting evidence, not emphasized in past papers. This frame is part of a video sequence that is unusual since it includes a rapid S turn |

|

| Frame of bird's' reflection heading towards 5 o'clock, Left side of camera tree. Showing black body possibly black and white wings, white may be in rear half of chord. |

|

|

| Belted Kingfisher can have a surprisingly long aspect ratio but has different plumage and much shorter wing span, 22" AMKI to 30" IBWO, as shown above (see papers by Collins) |

Bird

|

| Bird moving to 2 o'clock,. if you rush adjustments on image you may lighten up trailing white half of wing without seeing the dark front half of wing. This frame was "brightened". |

|

| Bird moving to 2 o'clock,. if you rush adjustments on image you may lighten up trailing white half of wing without seeing the dark front half of wing. This frame was "brightened". |

Here, used for the first time, is a draft simple, rapid method to assess if the white "W" pattern of a N Campephilus species is in a frame or picture.

Simply zoom in slightly on the ORIGINAL jpg if possible for best results. Then trace a line across the bird's dorsal side along any white area on the white area midline, with only a total of 1 or 4 straight strokes, from wing tip to body (if white on tail or body) to wing tip. Only 1 or 4 straight strokes must be used and one retrace line can be used to complete the process.

To eliminate bias for important cases or IDs three intelligent but unbiased parties who know nothing pertinent about large woodpeckers should be given instructions and then asked to complete the 1 or 4 lines step. Analytical software can also be used.

The "W" pattern can be harder to see in the field or document with a camera as the sight line shallows. As the sight line becomes more obtuse the Campephilus white dorsal stripes will gradually "merge" or "disappear" and the pattern can become a side wise "T", a modified "I" or an "I".

Here are 3 frames picked for their better resolution from the 2008 video; these are correlated with the bird passing close to the tree as one would expect. The sight angles for the three frames were ~ 110, 112 and 130 degrees respectively.

Here are the frames:

|

| Suggestion of "W" in dorsal pattern of an IB here. Bird heading towards 2 o'clock. This is similar to other poorly resolved frames (AR 2004) determined to be IBWO and not PIWO after extensive review by 17 authors. |

Inconsistencies with BEKI:

wing beat Hz may be different than video

plumage pattern inconsistent with video

no white patches in tip of darker wing

no large white "bar" across trialing primaries and secondaries as seen in video

no contrast between white neck & much

white pattern does not match simple model for poorly resolved Campephilus, see below, (model in testing only).

|

| Ivory-billed, East Texas decades ago. Circumstantial evidence supports this being a real IBWO. |

|

| East Louisiana |