However after examining Thompson's assertions on drumming, carefully listening to the Singer audio and reviewing some of the Ivory-billed literature there is no firm evidence the species drums versus some tap-drumming or displacement behavior tapping.

Although the magazine piece is an entertaining read for those interested in historic lore, it is well supplied with opinions, moral inconsistencies, rationalizations, scientific errors and no doubt fiction that is thinly and unsuccessfully hidden amongst his many adjectives, beliefs and pursuit of "knowledge" assertions. The writer is best known for his fiction novels.

The liberal substitution of a hyphen with an equal sign in the story's title is a precocious warning of the loose literary and scientific license to follow. As one progresses through the piece and certainly by its terminus, one is mystified how someone can be so tone deaf to their flippant ethical reversals in such a short piece. The destruction of roosts, taking of eggs and killing of adults of even a known rare species was rationalized from a menagerie of choices. These manic urges always curiously slanted towards destruction and the likely self interests of this 19th century intruder-------it was claimed to be done out of curiosity, in the name of knowledge, or that the species was doomed.

The seeker of stories is led to his quarry before a more conservation centric attitude had germinated in the country. Frank Chapaman who took many Ivory-bills for collections soon helped turn the tide; the legendary Christmas Bird Counts blossomed from the prior, cold period of rampant shooting of birds. Harsh judgment of Thompson's actions which were common at that time should be avoided; the examination of his Ivory-billed musings and scientific fabrications are more central for the Ivory-billed.

But he was an educated man, raised around moral clergy; certainly, aware of right and wrong. There is a common nexus to how detractors synthesize modern Ivory-billed evidence---Thompson was short-sighted as is today's skeptic. They cannot accurately and convincingly explain away the stack of evidence that the Ivory-billed persists or may persist but rather conjure up serial improbabilities as a "solution". Unethical, mis-leading and nonsensical explanations can seem congenital for some with various personal or monetary motives driving it.

As Theodore Roosevelt, who saw Ivory-bills said about the robber barons abusing our natural resources,

" I am amused at the short-sighted folly of the very wealthy man and I am deeply concerned to find out how large a proportion of them stand for what is fundamentally corrupt and dishonest."

Like present day skeptics Maurice must rationalize his actions with inaccurate procrastinations. He states the bird will probably be extinct within years (written in 1885, and off by several thousand percent and counting, (Fitzpatrick, et al. (2005), Hill et al., suggestive evidence, (2006), Collins, (various years), Latta et al., (2022).

Right from the origin something seems amiss as Ivory-bills were rarely or ever known to nest in the same hole from the prior year. And who would lead an esteemed guest deep into the swampy forest without a prior and recent scouting trip. This was one exceedingly lucky group of amateur oologists to go out and immediately find a nest almost to the hour of egg laying. Conversely, if true, it was an unlucky group of rare woodpeckers.

Thompson continues his tale by proclaiming he could have shot the birds as they came to their alleged nest but he is "not an assassin" and will spare the magnificent adults. His use of assassination soon after President Garfield was shot and his direct connection to President Hayes, who used some of Thompson's writings may not be trivial.

Several days after beginning to observe this nesting pair he was led to, (exact details of such a rare event are suspiciously lacking for a naturalist writer) the Lord God birds finally notice him. Before that there's not a word about the pair exchanging parental duties, time on the eggs, bill clasping, etc. that any populist author would have greatly expanded upon for the enjoyment of the naturalist or moralistic family reader. He says nothing about whether the bull or hen sits on the eggs overnight. Not a syllable is scribbled.

|

| Led to "nest". Certainly sir, I can carry you to where the birds had their nests last year. |

He vaguely relates the log gods are now harder to observe after they discover his hiding spot. There is no real answer of why he could not have come back in two or three days, with better concealment, in a different spot, if incubation was occurring.

He more than glosses over that his presence near the nest has likely caused the birds to abandon the nest and eggs; there is no donated honesty forthcoming towards his audience that is ignorant of the implications; there are no hints or concern from him.

|

| Satilla River GA area today in location where Thompson reported the pair, rather narrow low DBH forest corridor along river today precluding modern occupancy |

By his own musings it's easily deduced that his proximity to the nest has likely caused the abandonment. But he needs to quickly change the subject and be absolved, and cleverly brings up the need for "knowledge". So for his audience's education the eggs must be collected, which were no doubt non-viable if that gaping story is somehow correct.

He relates to his constituents that it was a hard decision; not really since he must have known the eggs were no longer viable if a bird was not on them during the cool to cold, late winter nights and evidently in the day. But few in the 1885 audience might have noticed this slight of word. One has to wonder, but not for long, if he would have taken the adults if given the chance; luckily these birds had disappeared.

At the end of the article he says somewhat joyfully, that "several trips" later he had shot an Ivory-billed and had now completed another contradiction of his own alleged and vacuous claims of not being an "assassin". Incredulously he relates that the valuable specimen was lost due to some mysterious accident just like the Ivory-bill eggs were lost in Georgia as you will read here. On two occasions the author, who claimed not to be the harbinger of death, directly destroys 5 eggs and one adult, disturbs an alleged pair and may have disturbed other Ivory-bills all for no real scientific gain but this rather baffling article that is rife with inconsistencies, possible reach out to the popular creationism adherents of the time and their priorites. All of this with career enhancement for Maurice in the foreground.

Near the Satilla River, Georgia Maurice and the "cracker" make a tree ladder, dismantle the nest's mouth to get at the eggs, writes microscopic details about the eggs inferring they could have easily been in his hand and then he carelessly drops the 5 valuable treasures. He claimed the eggs were only ~ 21 feet above the ground in this bizarre and incongruent accounting of the loss of something he alludes to have been pursuing for many seasons, years or even decades.

The date of this event is biologically implausible to have been in 1885 and be in print by April of that year. This series of events, even if true certainly, did not occur that year. Tanner (1942) lists the event as around 1885 as he was no doubt incapable of deducing the year from this vague work. Hasbrouck (1891) notes the event but incorrectly attributes finding the nest to Thompson who was actually led to the nest. Hasbrouck states the birds were in the "Okefinokee swamp but lacks the important item, the date."

During the time between the Hasbrouck and Tanner's writings, over 47 years, the location has moved ~ 20 miles east to a small tributary of the Satilla River but Tanner is also unable to relate the exact date.

Hasbrouck:

Hasbrouck's paper in the Auk (1891) is a notable and often referenced Ivory-billed work. In reading the paper it is silent on whether he actually every spoke to or met Thompson. He references only "A Red-headed Family" as the source for the two of the ~ 68 location records in the 1891 paper. Three percent of the records in his paper are made by Thompson; there seems to have been minimal due diligence on these two records other than reading some or all of "A Red-headed Family". For some reason Hasbrouck writes that Thompson found the Georgia birds when no such claim is made in the magazine article (1885).

Records of Ivory-bills, 1891

One could accept Thompson's complicit participation in the prevailing but ignorant lack of conservation ethics of the nineteenth century if he at least began to share some in depth knowledge of the Ivory-billed. He only partially delivers with some correct verbiage on plumage. No doubt he had some experience with seeing live and dead Ivory-bills or those who did.

He continues and unfortunately we get a narrative of kenting, double knocking and drumming on the nest tree that is not supported by the scientific literature from any century; it makes scant biological and behavioral sense. Birds in general are fairly quiet and secretive around the nest tree unless a predator is threatening the eggs, or the adults. Maurice was hidden. He describes a relatively noisy or busy acoustical scene around the nursery tree but their is no biological context during these observations that supports why these counter adaptive signals that attract predators would have occurred.

It does make a granular and emotive script as he claims to hear the Ivory-billed near him on the bole communicate with its mate deep in the swamp forest. One can imagine hearing the sounds of this massive woodpecker and its mate knocking, kenting and then "drumming" to each other in some unknown dialect known only to them and not man.

But well researched books on Thomson reveal that he "had certain severe physical and intellectual limitations which led to emotional instability".

Thompson Biography Review

Thompson's tale is a compelling story, but maybe that is all it is.

These various accepted acoustical signals of Ivory-bills, and woodpeckers away from a nest would have been known by Thompson from most of the early literature and field discussions with various colleagues, naturalists, hunters and rural folk. Less known then, was that Ivory-bills, like many animals, are not that vocal around their own nests, for obvious reasons, unless disturbed.

But as a foil to the "silent around nest narrative", is the very lengthy and methodical observations of breeding Pileateds that meaningful drumming does occur on their nest trees. According to Kilham (1959) the drumming has a communication function between the pair. Was Thompson the only person to be gifted the chance to see, under the needed clandestine cover, a pair of Ivory-bills drumming on a nest tree?

Almost all or all the literature, and the 1935 Singer recordings have what I consider displacement behavior or at best drum-tapping. The tapping seems to be roughly associated with notes other than typical kents; these are the lower softer yent-yent-yent of nesting birds (Tanner, 1942 p 61). To hear these notes go to this link and listen at :11, 1:58, 3:19. 3:36, 4:11, 4:16, 4:45 and 5:15. Note that one of these, perhaps the last, is the acoustical sound recording of the wing beats of an Ivory-billed. The frequency of these wingbeats coincidentally matching the wingbeats in the AR (2004) Ivory-billed video and the SE LA (2008) video.

Drum-tapping Singer 1935

Maurice was originally an attorney, then an engineer, but became a talented and popular novelists, poet, writer, archer and naturalist. I take it as literary license and style to build a story line and create anticipation as the birds call, knock and "drum" to each other unseen and separated by distance. The "King" and "Queen" dramatically move towards the tree the author was led to and now eagerly awaits their arrival.

Concerning drumming there is a proclivity for inexperienced and even some experienced observers of animals and specifically woodpeckers to mistake the context of what is occurring. Confusing displacement behavior knocks, a series of knocks sounding for insects or a series of blows testing for resonance for a needed future double knock spot, for territorial drumming is common place. The serial tapping and short series of woody notes on the Singer Tract tapes of agitated birds with a potential predator (people) near their nest is perhaps the classic example of displacement behavior, or drum-tapping, often mistaken for drumming. Another explanation for the drumming is also plausible.

Recently several of the hundreds of Ivory-billed frames were found in the evidence of Ivory-billeds in the Louisiana preprint paper (2022) to show courtship and mating ( Ivory-billed Woodpecker Mating ) . While researching Ivory-billed and Pileated behavior scientific evidence was found that Pileateds do an unusual drum on the nest tree (Kilham, 1959). Other woodpecker species also drum on the nest tree; Thompson's description, if accurate could be describing a specific IB communication that is associated only with the nesting tree.

Kilham:

A nesting Ivory-billed with competing hormones that motivate an animal towards two different behaviors, often results in an action that is unrelated to either motivation. A predator at an Ivory-bills' nest can cause a bird to attack or swoop at the predator, move far away or even abandon the nest. None of these are that desirable to an animal since these responses can or will result in death for the Ivory-bills and/or their progeny. Resultant can be nervous knocks seeming like a drum that are not intended to address either motivation. The tapping or odd series of quick knocks might just be a way to release tension. The Thompson article may, and the Singer Tract audio tapes do, portray likely displacement behaviors in the form of drum-tapping, knocks or some series of fast knocks occasionally misinterpreted as drumming.

Thompson continues to show that he had some but limited experiences with Ivory-bills with a series of fallacies, incongruities, odd statements or exaggerations as follows:

-- the bird only eats insects

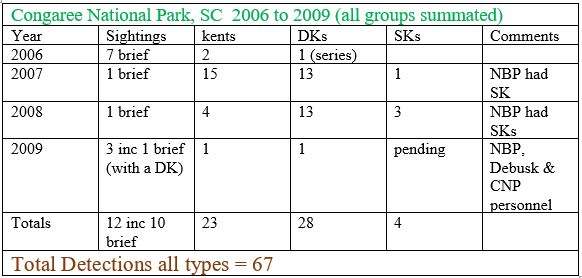

-- the alleged drumming reminds him of the minute Red-headed Woodpeckers snare when the double knocks (DKs) and SKs are known to very loud for IBWOs (in Congaree I heard, from ~ 200 feet, an SK that was so incredibly loud that I thought if it was an angry man with an axe I would never be found; the volume exceeded the incomprehensible for a bird). An IBWO "drum" would conceivably be thunderous but the author does not describe it that way.

-- other species of Picidae have less red in their head's than the king and queen Ivory-bills and are degenerate forms split from the Ivory-billed ( he seems to have forgotten about the Red-bellied Woodpecker and Red-headed Woodpecker, with more red)

-- he seems to taunt Wallace and Darwin for having no explanation for his various ideas on the "degeneracy" of woodpeckers

-- the author incorrectly describes the flight style of the species as being like other woodpeckers inferring undulation

-- he described the nest hole to be 5" circular which does not agree with other more serious authors that actually collected eggs or nesting specimens and saw and carefully measured nesting holes; they were consistently described as oblong, being ~ 20% higher than wide. The shape of a nest hole is no trivial matter; it is shaped to keep predators out by making it as small as possible but still allowing the male to get in. The author getting this so wrong despite being inches away from the entrance is a serious red-flag

|

| Notice the shape and size of all or almost all Ivory-bill Woodpecker nest holes does not agree in any way with Thompson's description. He alleges he had the nest hole in his hands. Also claims to have accidentally dropped the eggs with a bizarre story. Copyright Cornell |

|

| Possible Ivory-billed Woodpecker roost holes, 2005 Arkansas. Notice roost holes also do not agree with Thompson's size and shape description of his active IB nest hole. |

-- he closely describes the surface texture of the eggs which means he had them in his hand or close to his eyes and yet somehow, they wind up back in the cavity and are broken by some vague accident

-- never gives the date for the encounter in this article and Tanner and Hasbrouck were also unable to decipher it

-- he predicts in 1885 that the Ivory-billed will be extinct in a few years; he is incorrect by several thousand percent and counting. This shows that he was very unfamiliar with the field status of the Ivory- billed since Hasbrouck and others were receiving reports that there were still numbers of birds in a few locations. And of course 5 decades later there were at least 34 birds in the USA in the mid-thirties.

He also made strange predictions that the Red-headed Woodpecker might be nesting on the ground in less than 100 years

He gets possibly a bit whimsical with claims that Red-heads eat wheat.

\

and more

Because of our field research on single knocks, double knocks, kents and "displacement" knocks I was compelled to read several long works of Thompson's. He was a complex man. Shaped by his and family's active participation as

confederate combatants in the bloody

war you again find that ethics is malleable when

it is put up against his need and desire to entertain with a noble quatrain. After thousands of words this long Civil War poem manages to avoid with

room to spare the main point of why so many Americans died in that

conflagration. He is able to ignore slavery as he did the comparatively very minor taking of the

eggs and shooting Ivory-bills.

Doubtlessly he is an example of how

one’s experiences and self-interests shapes their perceptions and actions.

That long and

merciless struggle can instill rationalizations into life including decisions on collecting or

not collecting a rare bird and destroying or not destroying five unique

eggs or telling embellished stories about an event’s

details for educational, religious, career or entertainment purposes. How are we to fully understand a man who likely shot more

men and lost more friends to dismemberment than we have killed closet moths.

An Address Of An Ex-Confederate Soldier...

I was a rebel, if you please,

A reckless fighter to the last,

Nor do I fall upon my knees

And ask forgiveness for the past.

An Address Of An Ex-Confederate Soldier... - Maurice Thompson - My poetic side

Needing to find any possible clues of how the man valued truth to frame his new to science claims of Ivory-billed drumming, more time was spent reading his works. A 1888 novel was found next,

A Fortnight of Folly was read and by the third page the main characters says:

It was odd but not totally surprising to find, within minutes, that a main character closely fit what I had already observed in Thompson's treating of scientific truths. Telling was also the novel's open pretentiousness of writers and the competitive obstacles they must deal with to get ahead. The novel is about important writers, including Thomson who shamelessly places himself in the group who live gratis at a new mountain resort. Thompson's esteemed benefactor and owner of the resort has a mantra --

"He regarded anything which can be clearly described as fact".

Next was the novel The King of Honey Island that at least mentions the Pearl River, where I have written a scientific review of the 2008 Ivory-billed Woodpecker video captured by Collins:

Ivory-billed Woodpecker video analysis (Pearl River, LA)ysys

This novel mentions nothing about Ivory-bills even though Bay Saint Louis, MS comes up repeatedly. This is where Thompson alleges to have shot a male Ivory-billed sometime before April 1885. The specimen was lost with no details or sketch made because of an "accident". I hoped for the alleged deadly encounter to have some mention in this novel but found none. Apparently after visiting Georgia he headed south-west to coastal Mississippi where he took notes that eventually gave detail, factual background and accuracy to the Honey Island novel. There is another novel about Louisiana. This may be examined to learn more on drumming, story telling and Ivory-bills.

Another non-fiction title seemed to tickle the possibility of finding out if this novelist and naturalist deserved one title over the other: "BY-WAYS AND BIRD-NOTES."

Here we get a great look on how he perceives literature, nature, birds, facts and life.

Thompson respects the Greek Gods and elevates them to a penultimate arbiter of morals. He points out how they "bent the bow" to hunt. He shows the common morals of the time; although I never contemplated that classical fictional works about pagan deity would rate highly in a preacher's son psyche. He shows how he rates fictional literature as a real life guide; he values classical fiction highly.

Here below he explains that it's better to read about nature outdoors; this based on the unusual concept that if a literary work allows one to ignore the birds singing it's a good work.

He soon anthropomorphizes birds, then makes it worse with fiction that cuckoos are not inclined to make nests.

But here he rectifies himself with correctly asserting that Yellow-billed Cuckoos do indeed lay eggs occasionally in others species nests. But he immediately falters with unexplained predictions that the species will be a completely parasitic egg layer in ~ 1,500 years.

Here he asserts that some hawks may be correctly "far-sighted".

Here he waxes on about some mysterious mockingbird "mounting song" and its opposite. Unfortunately, no one else describes it this way, assuming these songs even exist.

While now reading my twelfth piece by Thompson it again struck me that he had in total only mentioned a heavy score of different bird species. The subjects were all common except for the Ivory-billed with a great concentration of them found in rural Northern Georgia. He seemed to be mainly a casual rural naturalist of farmhouse, sleepy fish ponds and town, in Northern Georgia, by today's standards. And he was led to a possible pair of Ivory-billeds.

He confirms his limited breadth of avian experiences, especially with passerines when he calls the colorful or adjective worthy North American bird a rarity. An experienced American birder can rattle off a hundred bird species that would counter Thompon's odd opinion.

Conclusions- There is no firm evidence that Ivory-billed Woodpeckers drum very loudly like other woodpeckers that are territorial; the Ivory-billed is not territorial.

Thompson's contributions to the Ivory-billed literature are minimal with parts of it right, wrong or possibly fictional. Some assertions, likely fictitious, are erroneous and should be substantially ignored. Because of these errors almost anything he writes beyond Ivory-bills fly, should be taken under advisement. That includes his claims of Ivory-bills drumming like "red-headed woodpeckers". Any actually seen series of knocks may have been displacement behavior or possibly drum-tapping assuming he actually saw an Ivory-billed.

He studied and worked almost his entire life outside of the Ivory-bills range, dying in 1901. His forays into Ivory-billed land seemed to be several winter trips of unknown length after 1880 and before April, 1885. These trips were likely "research" forays for some of his subsequent novels and other works based on fictional events in Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana, etc.

Although the author likely saw an Ivory-billed or a pair in SE GA, he was led to the birds; the location information coming his way likely via his geographical, political, journalistic, hunting and outdoor contacts.

The author's grand-father and father were Baptist ministers; Maurice may have been a creationist and the article indicates he thought Wallace and Darwin could not explain some of his observations on woodpeckers via their theories thought by many in the Unted States at the time to be heresy. He may have just been exhibiting career "marketing" in many of the questionable things he wrote or subjects he chose including A Red=headed Family.

The Indianan expends much ink on woodpecker relationships and the title refers to the Picidae family and not the poor Ivory-billed family he disturbed. He was trying to show there was divine design in the amount of red in the heads of woodpeckers with all species being "degenerate" to the Ivory-billed in this color category and perhaps within some hierarchy that he mysteriously correlates with the amount of red in the respective species.

Maurice valued points and eternal implications in this article that placed creationism much higher than evolutionary theory. His spiritual beliefs and the need to create an entertaining piece may have been more his focus than some "unimportant" points or the accuracy on drumming, the careful safeguarding of eggs which he neglects or even the actual existence of the Ivory-billed eggs. The 19th and 20th century Ivory-billed community (and some on Facebook 5/2022) may have failed to recognize possible sacred motives in this article for a popular magazine. Rationalizations may have led to "harmless" and "unimportant" observational exaggerations or worse fabrications that fit the higher cause according to frailties that we may all succumb to, very rarely, I hope.

It could be enlightening to see if Maurice eventually supported the soon to rise populist, William Jennings Bryan as a serial US Presidential candidate in 1896, 1901, etc. Bryan was a national populist and likely creationist, with him being involved in the, staged, Scopes-Monkey trial.

Thompson's interaction with any actual IBWO eggs in SE GA could be contrived, as no eggs or parts of eggs are in any collection despite him clearly knowing their rarity, but some of his detailed and correct observations must have had a primary source. He also incorrectly describes the shape of known nesting holes and the measurements erroneously according to all the literature.

He often found himself with various outdoorsman that easily knew more about the Ivory-billed than him, a man who had lived most of his life outside the Ivory-bills range with a late arrival onto the Lord God bird scene. He may have appropriated the information needed to formulate the strong granularity in the article, that when combined with his actual field knowledge and significant writing skills made the literary work possible, plausible and enjoyable to the great majority of his sponsors and readers.

The author also claimed taking an Ivory-billed near Bay Saint Louis on the coast of Mississippi (Tanner, 1942) but again a vague accident is noted that prevented even a sketch and the specimen was "lost" (Thompson, 1885). Very odd to have such a valuable specimen slip through one's hands by a man who knew it's monetary and scientific value.

He seems to have made 6, 7, 8 or more "excursions" in search of Ivory-bills claiming to have killed one male, viewed two live birds in SE GA and finding and destroying 5 eggs of the latter pair.

As far as the drumming he describes, there is no evidence that IBWOs actually loudly drum in the typical signaling context. There is few if any writings that drumming was or is occurring as an advantageous acoustical clue or method for finding IBWOs in the modern field. If it does occur it may be what is called drum-tapping as some signal between birds, sounding substrate for an upcoming loud single or double knock or displacement behavior.

Our company's IB field work has afforded me and teammates the opportunity to hear single knocks, double knocks, kents, of Ivory-bills and thousands of drums including hundreds of Pileated drums. I have never noticed a heavy, loud drum that I or others attributed to anything but a Pileated Woodpecker.

As far as Thompson's numerous mistakes, even with common species, they confirm that he had limited field experience with many species of birds and Ivory-bills but enough to make some observations that are true in an entertaining and imperfect story at best.

Original Article Link:

A Red=headed Family.